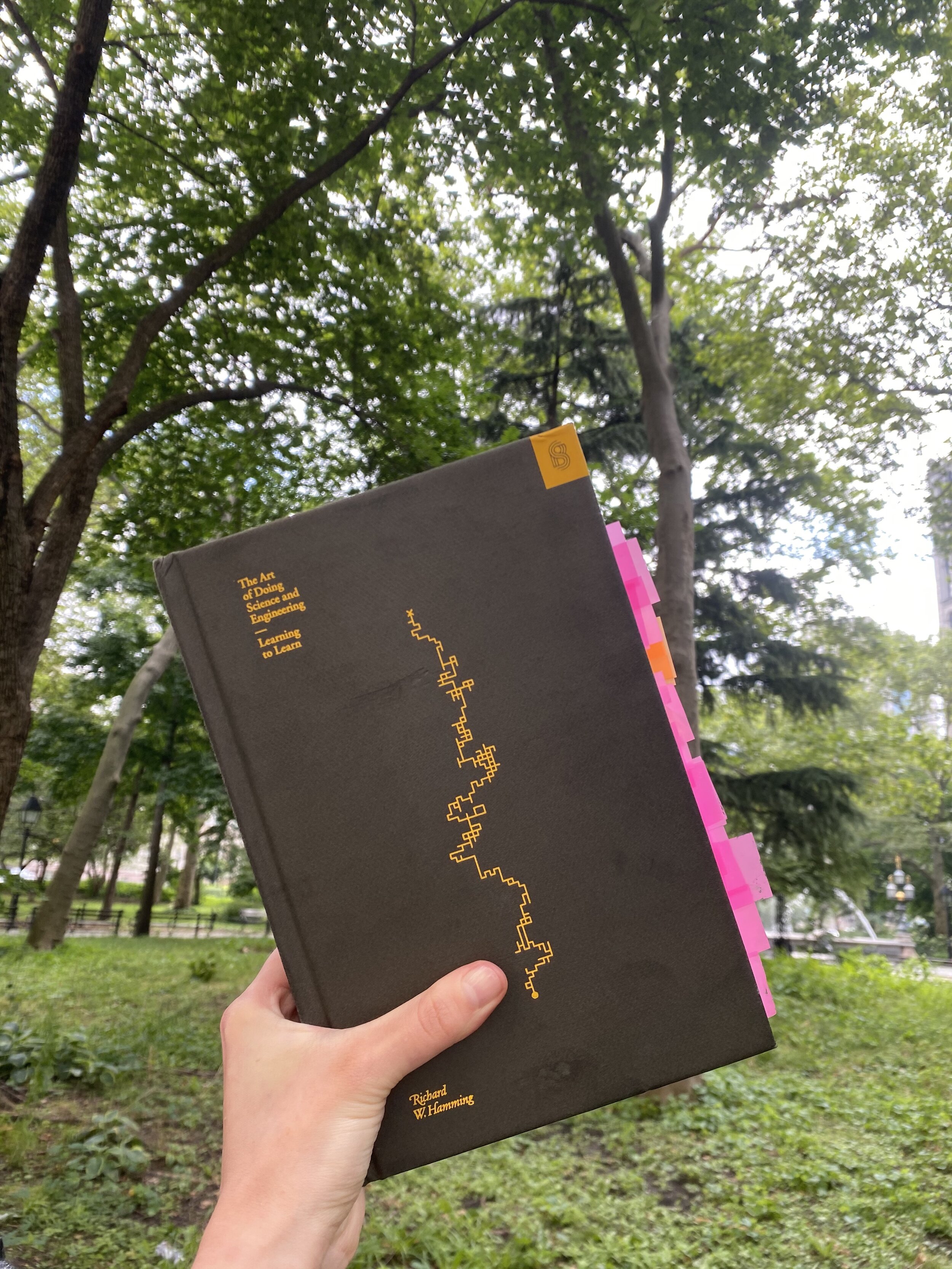

Richard Hamming invented a lot of cool stuff. He also wrote a book sharing advice on inventing cool things. In his book “The art of doing science and engineer: Learning to Learn” he paints vivid images of greatness and it’s unapologetic pursuit. Not only it allowable to aim for greatness, it is cowardly not to. The book is made extra special as he frequently refers in the book to the year 2020, trying to anticipate marvelous inventions. While he has missed the mark on a lot of his forecasts, I find the foundations that he cites to be timeless. Here are my favorite take-away conclusions:

1. “Luck favors the prepared”, indeed a quote that is the main theme of this book.

2. Throughout the book he reiterates that it is important to polish and develop “style”. He suggests benchmarking on great scientists. Having a style becomes critical, because he considers promoting and presenting ideas as important as the idea and research itself.

3. There are no shortcuts to the top - no hacks can compete with learning and work.

4. What is technologically feasible and economically better, is restrained by legal, social and economic conditions. Just because it can be done doesn’t mean it should be or will be done. (Hence promoting your ideas and collaborating becomes crucial for the ideas to succeed”.

5. He cautions about experts and says “what you did to become successful is likely to be counterproductive when applied at a later date.” He warns that as we accumulate experience we are becoming less open to breakthrough and experiments.

6. Defining what’s to measure sets the outcomes. “Accuracy of measurement tends to get confused with the relevance of measurement. You get what you measure in the end.”

7. Open door policy. Open ideas everything.

The overarching summary of the book can be grasped by reading his essay “You and your research”. However I would highly recommend it to anyone in the search of the meaning of work, research and generally life.

> “Civilization is merely a thin veneer we have put on top of our anciently derived instincts, but the veneer is what makes it possible for modern society to operate. “

Richard W, Hamming “The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn”

HTML/CSS drawing in the style of an 18th-century oil painting. Hand-coded entirely in HTML & CSS. More at pure-css.com: [Pure CSS Francine - 🖼 CSS-ART.COM](https://css-art.com/pure-css-francine/)

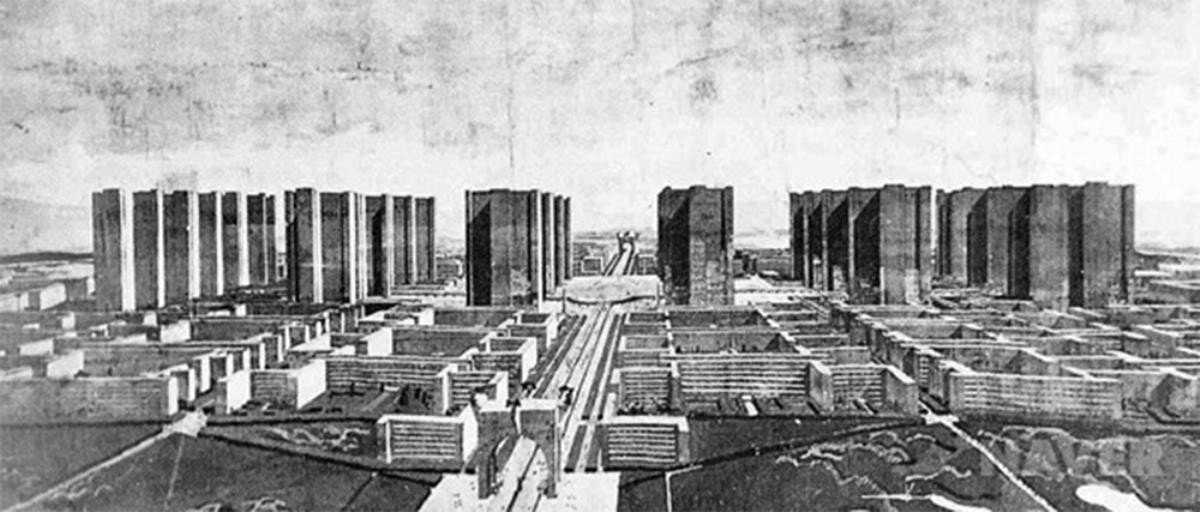

Ville Radieuse, or more commonly known as Radiant City was a rational take on urban planning by Le Corbusier

This spring I have finished a book that has been on my reading list for quite some time: Jane Jacobs’s “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. I have been procrastinating to compile the notes. However this week I have encountered multiple articles (from The Atlantic to Politico ) that tried to forecast the changes of the cities due to the pandemic. Structurally, streets, avenues and boulevards remain the same, but one can “feel” the change of the atmosphere and pace. In NYC the place of cars is taken by pedestrians, cyclists and electric buses, while gardens, playgrounds and restaurant terraces occupy former parking spots. I anticipate Jane Jacobs would have been thrilled to see these changes since she was. Here are some additional pearls of wisdom about her book, that I think is rarely considered in city planning (unfortunately):

* On engineering social turnaround: “It is fashionable to suppose that certain touchstones of the good life will create good neighborhoods—schools, parks, clean housing and the like. *How easy life would be if this were so! How charming to control a complicated and ornery society by bestowing upon it rather simple physical goodies.* In real life, cause and effect are not so simple.”

* On crowds and morality: “People gathered in concentrations of big-city size and density can be felt to be an automatic—if necessary—evil. This is a common assumption: that human beings are charming in small numbers and noxious in large numbers… On the other hand, people gathered in concentrations of city size and density… are desirable because they are the source of immense vitality… *a great and exuberant richness of differences and possibilities, many of these differences unique and unpredictable and all the more valuable because they are.*” -> in 2019 The Atlantic wrote an article which made the same conclusion -”tourism” is the other person’s vacation.

* On the ugliness of “order”: “Homogeneity… poses very puzzling esthetic problems. If the sameness of use is shown candidly for what it is—sameness—it looks monotonous. Superficially, this monotony might be thought of as a sort of order, however dull. But esthetically, it unfortunately also carries with it a deep disorder: the disorder of *conveying no direction*. In [such] places… you move, but in moving you seem to have gotten nowhere. North is the same as south, or east as west… It takes differences—many differences—cropping up in different directions to keep us oriented.”

* On designing for humans: “Genuine differences in the city architectural scene express… [Jacobs quoting Eugene Raskin:] /‘the interweaving of human patterns. They are full of people doing different things, with different reasons and different ends in view, and the architecture reflects and expresses this difference…Being human, human beings are what interest us most. In architecture as in literature and the drama, it is the richness of human variation that gives vitality and color to the human setting… Considering the hazard of monotony… the most serious fault in our zoning laws lies in the fact that they _permit_ an entire area to be devoted to a single use. “

Recommended Reading:

](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5badfa2ef8135a3bb3c5dc34/1594588743792-50N28SC3DONX1RDL3E8H/Screen+Shot+2020-07-11+at+9.00.09+PM.png)